Morning Thinking is an integrated reading, writing, and thinking routine that is simply executed but provides complex results. It is efficient and almost never feels formulaic. I use it daily as the first task of the morning. Students do morning thinking independently for 15-20 minutes while everyone is getting settled. It allows for high quality thinking and writing in a short time period while the day is just starting.

I use the same google doc for the Morning Thinking routine that I do for The Way to Start a Day routine–that allows me to have a boilerplate structure and then replace it quickly with that day’s thinking work. There are four variations that I use: quotation, poem, comic, and math eyes. I use the quotation variation most regularly.

Quotation Variation:

- Boilerplate Directions: Write the quotation in your Morning Thinking notebook precisely as it appears. Then answer each of the following questions: What does the quotation mean? Do you agree with it? Why or why not? How could this quote change the way you think, speak, and act?

- Quotation: I choose a different quote each day. I might choose one that builds community or one that addresses a community issue we’ve been struggling with. I might choose something that relates to current events, a read aloud, or a unit of study. I might choose a quotation from a person of note who we have been studying or is in the news. At the beginning of the year, while I’m trying to build writing stamina and familiarity with the routine, I try to choose more direct but still thoughtful and relevant quotations. As the year goes on, I try to choose something that is challenging but within reach for most students. I’ve had several classes who get really excited about quotations and start researching to bring in their favorites or even write their own that the class then writes about.

- Writing Goals: I emphasize writing the quotation precisely as it’s shown on the SmartBoard as a way to practice spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and attribution of words. This is a great place to practice conventions in context. Each of the boilerplate questions adds a level of increased complexity and abstraction. Students who need to spend more time figuring out the literal meaning of the quotation may spend more time on the first couple of questions; students who are ready to engage with more abstract levels of thinking may spend more time on the last couple of questions.

- Sharing: Once I’m ready to start instruction for the day, I call students to the carpet. They don’t bring their notebooks but simply use their writing as prethinking for discussion. I always start by talking about any unfamiliar words. Then we dig deeply, talking about the big themes, ideas, and how the quotes relate to our lives and world. I encourage students to be honest if they disagree with a quote and give them an opportunity to share their thinking. This is a good space to safely and gently teach kids to disagree and argue using reason and respect. We also point out interesting spelling patterns or new punctuation. Depending on the complexity of the quote and the engagement with it, we generally spend about five minutes reviewing their morning thinking.

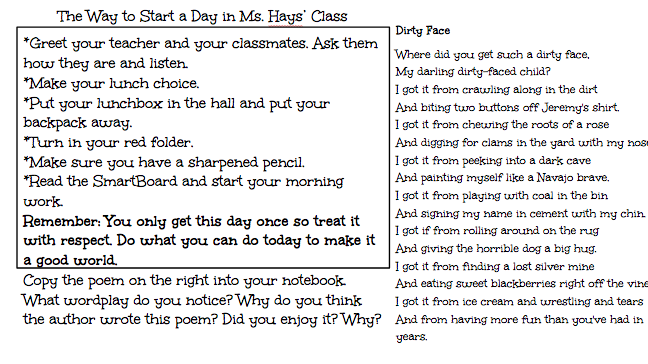

Poem Variation:

- Boilerplate Directions: Write the poem in your Morning Thinking notebook precisely as it appears. Then answer each of the following questions: What do you think the poem is about? Why do you think the author wrote it? What word play do you notice in the poem? Did you enjoy it? Why or why not?

- Poem: Because a poem is generally longer than a quotation, we take 2-3 days to work with one: copy it the first day and then write about it the second and third days. I try to do a couple of poems each month. I try to choose a variety of poems: popular kids’ poems from authors like Shel Silverstein or poems that relate to our units of study (I’ve tried to find good poetry books related to each thematic unit of study). I also make sure we do several complex literary poems throughout the year: “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” “Ozymandias,” “The Road Not Taken,” “Allowables,” for example. Each of these are difficult but still age appropriate for the middle grades and allow them to do some deep literary analysis with short text.

- Writing Goals: I emphasize spelling, punctuation, and capitalization in poetry, but also add in specific features of poetry. Having them copy the poems precisely allows me to introduce and then reinforce vocabulary more specific to the form, such as line breaks and stanzas. We talk about different kinds of word play as the year progresses so their ability to identify and write about rhyme, simile, metaphor, idioms, alliteration, symbolism, etc. continues to develop throughout the year.

- Sharing: Our sharing work with the poem is a bit more complex. The first day, I start by asking if there are any words that they don’t understand how to pronounce or define and we discuss those. Then we have a perfect opportunity for shared reading–sometimes I read it aloud first and then we read aloud together, but if the poem is fairly simple we dive right into shared reading. We talk through any word play we can identify together. And then we do a basic discussion of what it means. The second day we discuss the poem, we begin with shared reading again, working on fluency, expression, and even gesturing. Then we dig into the deeper aspects of the poem–analysis of why the author wrote it and student evaluation of whether they like it or not. We also try to identify the purpose of the genre over these conversations–why did the author write this as a poem instead of as prose? Typically, these conversations take about ten minutes each day.

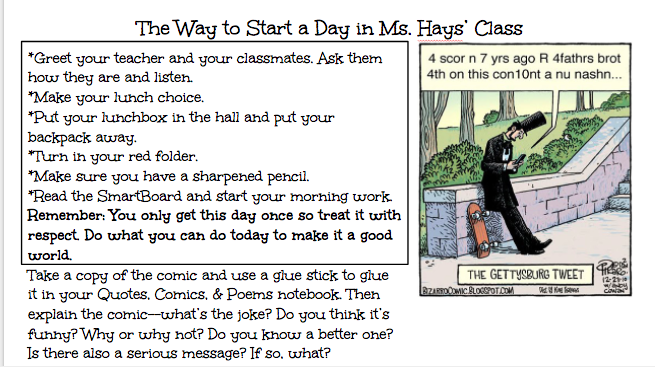

Comic Variation:

- Boilerplate Directions: Take a copy of today’s comic and paste it into your Morning Thinking notebook. Then answer the following questions: What’s the joke? What word play does it use? Do you think it’s funny? Why or why not? Can you use it as a model to come up with your own?

- Comic: I typically try to use this variation on Fridays or the last day of school before a break. I try to find comics that are related to our content in some way or just fun ones that have floated across my social media (try Grammarly as a good resource–or just google comic about whatever topic you’re studying). Then I download it and make each student a copy of it. Obviously, be careful that you are choosing comics that are appropriate for your students.

- Writing Goals: The writing for this variation is more creative and less structured. It helps practice identifying word play and features of humor (puns, rhymes, metaphors). It also gives space and time for artists and jokers to shine!

- Sharing: The sharing about comics is usually pretty quick. Do be sure to name kinds of word play and features of language that make the humor (here’s a great place to talk about homophones in a less boring way!). Also, give your budding comic artists time to share under a document camera. We usually take about five minutes to share about comics.

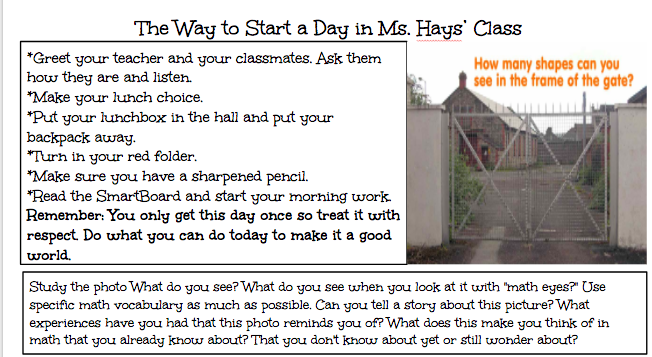

Math Eyes Variation:

- Boilerplate Directions: Study the photo on the board. What do you see? What do you see when you look at it with “math eyes?” Use specific math vocabulary as much as possible. Can you tell a story about this picture? What experiences have you had that this photo reminds you of? What does this make you think of in math that you already know about? That you don’t know about yet or still wonder about?

- Math Eyes: Inspired by the Have You Got Math Eyes? initiative, where you can find numerous photo examples, project ideas, and lesson plans. This is a great way to develop connections between real life and math, math vocabulary, math writing. As your students build experience with their “math eyes,” have them create their own posters for the class to write about.

- Writing Goals: I worry less about conventions with this variation and more about development of mathematical expression, thinking, and vocabulary in context. This is a great spot to build mathematical vocabulary and talk about specific mathematical definitions of certain words that also have common definitions (plane, point, odd, negative, etc.). Consider having children use a colored pencil when they share to box or add in specific math vocabulary.

- Sharing: This is a great space to build a positive math mindset by showing students how important math is and how much they can observe and already deeply understand. Support students as they build specific math terms and thinking into their writing and speaking. Depending upon student familiarity with the concepts and how you are integrating the thinking routine into your math content for the day, sharing should take 5-10 minutes.